NotebookLM + PBL

Why Your Student Portfolio Should Generate New Thinking

I’ve taken some time to rest and build a workshop for teachers about NotebookLM and student portfolios. I keep thinking that we’ve fundamentally misunderstood what portfolios are supposed to do.

We treat them as storage. Collections. Things students curate and then forget about.

I’ve been researching a book called, How to Take Smart Notes by Sönke Ahrens, and he describes something called the Zettelkasten. It’s basically a system where individual notes don’t sit alone. They connect. They feed into each other. They become generative.

Let me get specific about what this actually means in education.

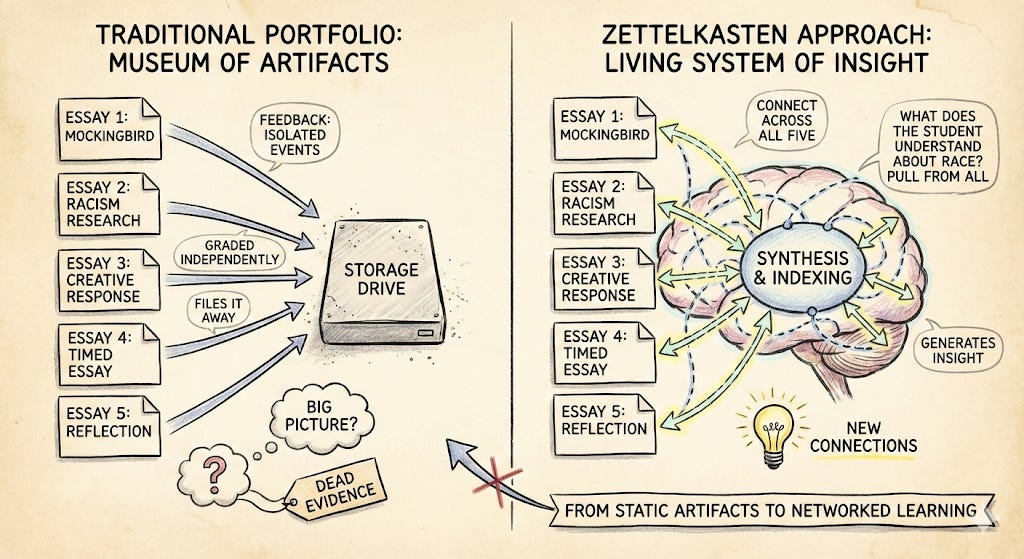

Right now, imagine you’re teaching junior year English. Your students write five essays across the semester. First one’s an analysis of To Kill a Mockingbird. Second one’s a research paper on systemic racism. Third is a creative response. Fourth is a timed essay. Fifth is a final reflection.

How do you grade these? You probably read them one at a time. Essay one gets feedback. Essay two gets feedback. They’re separate events. Each one is graded independently. You might write comments like “good analysis” or “needs stronger thesis.” Then the essay gets a grade. The student files it away or throws it away.

Those five essays probably show something massive about that student’s thinking. Essay one might show they struggle with textual analysis. Essay three might show they actually understand characterisation deeply when given freedom to explore it. Essay five might reveal they’ve been thinking about systemic inequality all semester but never had a place to articulate it.

Except you never see those connections because the essays aren’t connected. They’re isolated artifacts.

With a Zettelkasten approach, a portfolio works differently. All five essays upload into a system. Not just a ‘storage’ drive but they’re indexed. They connect. A teacher, or the student themselves, can ask: “What does this student actually understand about race? Pull from all five essays.” The system doesn’t just retrieve the one essay about racism. It synthesises across all five because they’re networked.

Right now portfolios are museums. You add something in October, it sits there. Static. A student finishes a research project, uploads the final paper, and that’s that. The artifact just... exists. It doesn’t connect to anything. It doesn’t generate insight. It doesn’t create new work. It’s evidence of learning, sure, but it’s locked evidence. Dead evidence.

The traditional model asks: what’s your best work? What demonstrates mastery? So students curate. They optimise. They exclude the rough drafts, the failed experiments, the messy thinking. The portfolio becomes a highlight reel.

Then it goes into a folder.

What if portfolios worked differently?

The Shift From Museum to System

Ahrens makes this argument that writing isn’t something you do after thinking. Writing is thinking. “Writing is not the outcome of thinking,” he says. “It is thinking itself.”

Apply that to how students build portfolios. Right now we ask them to write something, then add it to a collection. We’re treating the portfolio as post-thinking storage. What if we flipped it? What if the portfolio became the space where thinking actually happens?

With tools like NotebookLM, you can feed it everything in your portfolio, research papers, project files, lab reports, photos, audio captures, raw notes, sources. Then you ask it questions. It synthesises across everything. It finds patterns. It generates study guides. It can create podcasts from your material, even fancy slide decks with minimal guidance. It takes what you’ve collected and makes something new from it.

That changes what students collect. If your portfolio is just a showcase, you include your best six things. If your portfolio is a working system, something you actually use to think with, you collect differently. You include comprehensive materials. Your notes alongside your finished paper. Your sources. Your iteration process. You’re building something that lives and connects, not something that sits and impresses.

Ahrens talks about note-taking as building a “network of ideas.” A good portfolio becomes that network. Each artifact connects to others. New work can be generated from the connections.

What Happens to Assessment

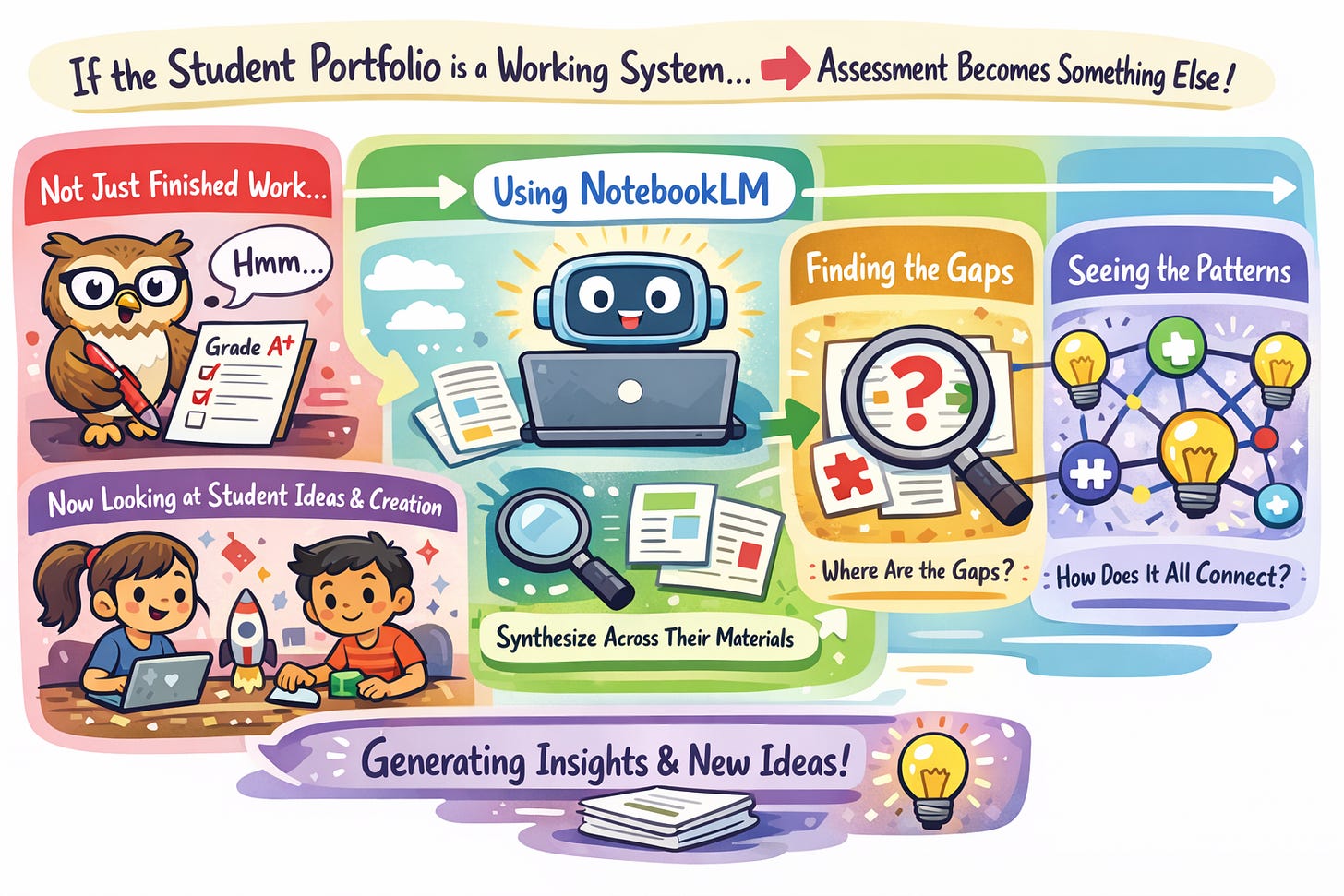

Traditional portfolio assessment is straightforward. You read the artifacts. You make a judgment. “This shows mastery. This demonstrates growth.” You evaluate what the student produced.

But if the portfolio is a working system, assessment becomes something else. You’re not just reading the finished work anymore. You’re looking at what students can generate from that work. You use NotebookLM to synthesise across their materials. You ask it to find gaps. You see what patterns emerge when everything connects.

A student can’t fake understanding in that situation. You can write a polished final paper and hide gaps. You can’t hide gaps when you’re forced to synthesise across everything you know and generate something new from it. Ahrens writes about understanding this way: “The proof of understanding is in the ability to explain something to someone else.”

When students generate new products from their portfolio, podcasts, study guides, synthesis documents, they’re actually demonstrating their understanding with what they generate (if they can defend the generations of course). Not what they can write. What they can think with.

Making It Concrete

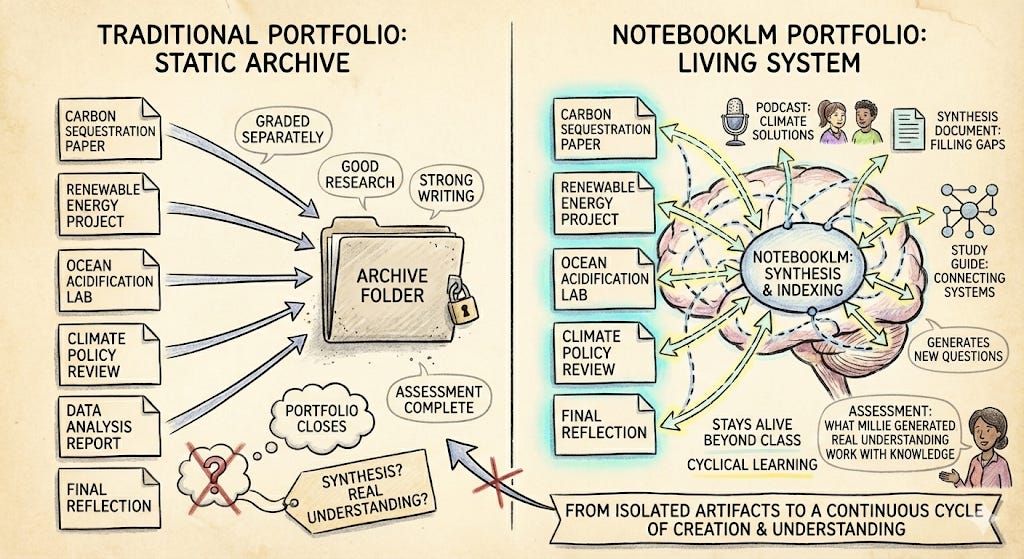

Let’s say there’s a student, Millie, taking climate science for a semester.

In the traditional model, Millie writes a research paper on carbon sequestration. She finishes a project on renewable energy. She does a lab report on ocean acidification. By semester end, maybe six artifacts. Assessment happens. Her teacher reads them. “Good research. Strong writing.” The portfolio closes.

In a working system, Millie collects the same materials. But everything uploads into NotebookLM. All her papers, all her project documents, her lab notes, her raw research. Then she generates from it.

She creates a podcast with a classmate discussing climate solutions using her portfolio as the source material. She asks the system to find what she doesn’t understand and writes a synthesis document filling those gaps. She generates a study guide that connects carbon science to energy systems to climate outcomes.

When her teacher assesses, they don’t just read the final papers. They see what Millie generated. They see how well she synthesised across her work. They see whether her understanding is real, whether she can actually work with what she knows, not whether she can format an essay.

That’s the difference. I believe this is what Ahrens means when he talks about working closely with your material, just like a teachers role with PBL to be present within the process.

The portfolio doesn’t stop after the semester. It stays alive beyond class. Millie can return to it. Someone else could build on it. It doesn’t archive her learning, it stays within a cycle.

What Changes About How We Build Learning

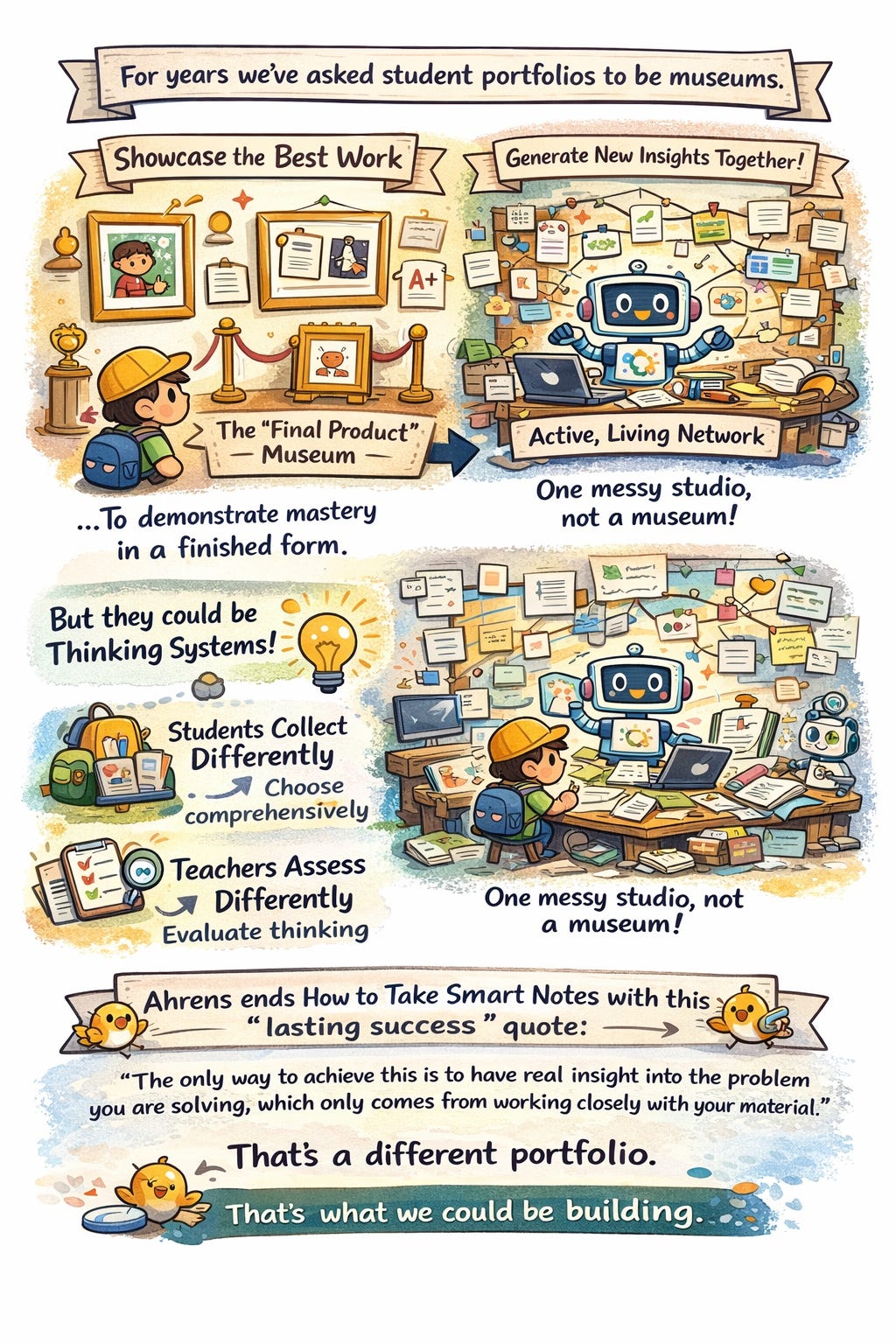

For years we’ve asked student portfolios to be museums. Places to showcase best work. To demonstrate mastery in a finished form. The final products on display. But they could be thinking systems. Active networks. Things that generate new insight because everything in them connects and gets worked with. If you go to any behind the scenes movie workshop, you see a messy studio not a museum.

Students collect differently when they know the portfolio will be productive. They choose comprehensively rather than curated. Teachers assess differently. They evaluate thinking, not just writing. Students produce differently. They generate from what they know rather than just displaying it.

Ahrens ends How to Take Smart Notes with something I keep talking about. He says: “The only lasting success is success that comes from the outside because it simply serves people’s needs better. The only way to achieve this is to have real insight into the problem you are solving, which only comes from working closely with your material.”

That’s what this shift does. It forces students to work closely with their material. To generate from it and consider what they are generating. To connect it. To actually think with it rather than just preserve it.

Tools like NotebookLM make this concrete. But the real change is reconceptualising what a portfolio does. Not an endpoint where learning goes to get evaluated. A living system where understanding develops through connection and generation.

A system with AI capabilities.

That’s a different portfolio

That’s what we could be building.

Happy 2026

Phil